Cumberland, B.C. was built on coal mining both literally and practically. Thousands of workers were employed and millions of tonnes of coal were exported over 80 years before the mines were shuttered, leaving deep holes in the ground and a deeper void in the village's economy.

The industrial foundations of Cumberland run deep. ACET researchers are determining how these now-abandoned coal mines under the village could generate geothermal energy to heat and cool buildings. Image: Cumberland Museum and Archive.

Now, thanks to a partnership with the University of Victoria-led Accelerating Community Energy Transformation (ACET) initiative, Cumberland is planning for a future built on clean energy that comes from the maze of abandoned mine shafts and extraction tunnels that snake beneath its streets.

Through the Cumberland District Energy project, ACET is determining how the water trapped in those tunnels could be used to produce geothermal energy that would heat and cool buildings.

With approximately 4,800 residents, Cumberland is a small municipality with a big community. Image: Sara Kempner Photography

Cumberland Mayor Vickey Brown sees this project as a step toward the reimagining of Cumberland already an attraction for nature lovers and mountain bikers as a clean, green outdoor adventure destination. It also represents a potential shift in how longtime locals, relative newcomers and visitors alike view the village.

"This is a way to highlight the history of Cumberland and bring it into a sustainable-future, clean-energy ethos," she says. "It's something that old Cumberland can be proud of, because we're using the waste of that old resource to transition to cleaner energy."

An old asset, a new opportunity for clean energy

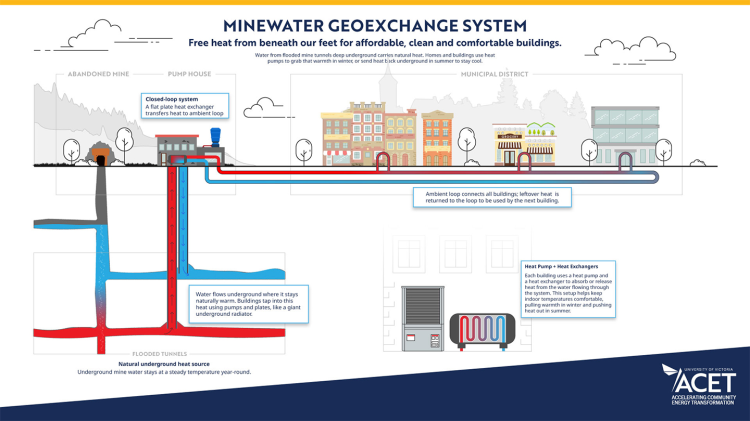

Using the temperature difference between the surface and the mines, closed-loop geoexchange systems circulate water to provide efficient, low-carbon heating and cooling. Illustration: Steven Hession

Here's how it would work: water trapped underground in the abandoned mines is cooler in summer and warmer in winter than the temperature above ground, explains ACET community energy planner and project lead Zachary Gould. Taking advantage of that temperature difference, heat pumps could use the water from the abandoned mines to provide heating and cooling to buildings at a relatively low cost and with near-zero carbon output.

"[The Cumberland District Energy project] is technically a very large ground-source heat exchanger," adds Emily Smejkal, a fellow with the Victoria-based Cascade Institute who specializes in geothermal energy.

Smejkal notes that having a network of mine shafts underneath the village means the entire town could access this clean energy resource.

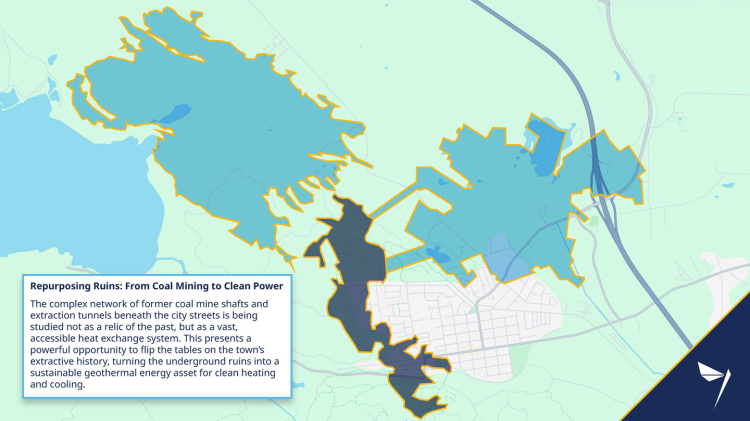

Geologists have mapped the extensive mine system running beneath Cumberland to better understand its energy potential for the community above. Image: ACET

To start, however, initial modelling of potential energy systems for Cumberland is focused on a proposed civic precinct redevelopment a community centre, municipal offices, even affordable housing and a large industrial zone closer to Comox Lake.

"It's been a big motivation to think about this energy system in the context of how we can reduce the costs of critical infrastructure and provide critical amenities for community members," says Gould.

"But it's not just an energy system," he notes. "It's an opportunity to look at resource extraction in a new way in a village that was built on extractive principles. This project could turn those ruins of extraction, so to speak, into an opportunity and a shared community asset."

Mining was historically the core of Cumberland community

From the Union Bay Wharf, millions of tonnes of coal excavated from Cumberland's mines were shipped globally, fueling economies as far away as Japan and establishing the region as a vital industrial hub for decades. Image: Cumberland Museum and Archive

From 1888, when the first mine opened in Cumberland, until the late 1960s, when the last one was closed, some 16 million tonnes of bituminous coal were excavated and shipped from the Comox Valley, says Dawn Copeman, a historian with Cumberland Museum and Archives. A wharf at nearby Union Bay loaded ships that were destined for international markets. Cumberland coal fueled steamships and heated homes. Coal coked in Union Bay was sold to smelters for lead and zinc production.

While the mines were the core of the local economy and community for decades, workers were exploited and their jobs were dangerous. Many miners died and many more were injured while companies sold a product whose burning contributed to climate change.

Using those same abandoned coal mines to produce clean energy doesn't rewrite Cumberland's history, Copeman says, but it does use that past to flip the script for its future.

Noting that a proposal in 2011 for a coal mine near Union Bay attracted "a lot of pushback," she says. In contrast, Cumberland's proposal to use its abandoned mines to produce geothermal heating and cooling provides a constructive opportunity.

"Being able to use something that's already there for heating, I think it's positive," she says.

'It's about reimagining these old relics of industry'

The history of the Cumberland geothermal project started more than 130 years after the first mine opened as a discussion among geologists who live in the region and gather regularly.

As Cory MacNeill, a Cumberland local and geologist, recounts it, a conversation amongst peers about the common issue of methane produced by the former mines evolved into chats about other geothermal applications for abandoned coal shafts. While the widely known application of drilling deep into the Earth to access super-heated water wasn't an option in Cumberland, accessing the water closer to the surface to offset the heat of summer and the cold of winter was.

And they had examples to follow. MacNeill notes similar projects have been established about an hour south in Nanaimo, B.C. and across the country in Springhill, N.S., another former mining town.

"It's about reimagining these old resources and relics of industry," he says. "It's really powerful to look at all of this mining and look at ways that we can benefit from it from a more environmental standpoint."

Highlighting the past while building a sustainable future

Mayor Vickey Brown dreams of a clean-energy future for Cumberland that honours its past. Image: Sara Kempner Photography

When Brown sat in on one of the geologists' discussions, she was already aware of the Nanaimo geothermal project at Vancouver Island University and of conversations between a previous Cumberland mayor and officials in Nova Scotia about their geothermal project.

What put the pieces together for her was an ACET webinar for municipal politicians.

"They said, We're looking for projects to work with municipalities.' And I thought, I have a project.'"

She explains there are two blocks of municipal property occupied by the village office, council chambers, public works and a rec centre that sit on top of the former No. 6 mine.

"I thought we could use this project as a way to figure out whether or not we could use geothermal for heating and cooling of the buildings because we want to redevelop the block," she says.

As a small municipality with apopulation of approximately 4,800, Cumberland doesn't have an engineering department to study such a project. Brown saw that ACET had what the village needed.

"We need their academic expertise and their capacity to help us do those business cases, and also do the [geothermal] exploration side of it," Brown says.

While the project was initially motivated by the desire to redevelop the municipal precinct, she says, if a pilot geothermal project proves to be successful and sustainable, there is additional potential in what Copeman calls the "vast labyrinth" of tunnels beneath the village.

Brown says providing cheap, clean heating and cooling to businesses could make Cumberland industrial land more attractive for development especially to enterprises that produce or consume considerable amounts of heat, such as greenhouses and food processors. Drawing businesses, she says, would mean adding jobs and contributing to the tax base, all potentially making the village more livable and sustainable for its residents.

"We haven't always worked very well with natural systems," Brown says. "But I think this is a model of using the tools and resources you have in place to look after the needs of your community. And I think that's far more resilient than the way we've done it in the past."